The Ultimate Atrocity

An account of Bergen-Belsen in Nazi Germany by Pembrokeshire author Tim Wickenden

As the aircraft landed on the hastily repaired strip – a Jock [Scottish] doctor raced up to us in his Jeep.

“Got any medical orderlies?” he shouted above the roar of the aircraft engines. “Any K rations or vitaminised chocolate?”

“What’s up?” I asked, for I could see that his face was grey with shock.

“Concentration camp up the road,” he said shakily, lighting a cigarette. “It’s dreadful – just dreadful.” He threw the cigarette away untouched. “I’ve never seen anything so awful in my life. You just won’t believe it ’til you see it – for God’s sake come and help them!”

[The words of comedian Michael Bentine – former MI9 officer who took part in the liberation, 75 years ago this month.]

Thirty years later, at age 12, I visited Bergen-Belsen, the place described by the Scottish doctor, and it changed the way I saw the world.

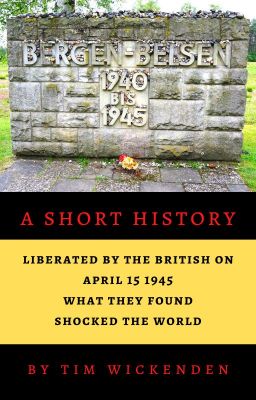

Now it is a peaceful open park some 1,400 by 400 metres, a monument, and I cannot imagine how it must have been as a camp. But there is no escape from the price paid by the minority groups herded there to die in conditions of inconceivable horror, for as you look around you see grassy mounds, mostly rectangular and huge, and each having a stone monument saying in German, Hier Ruhen 2,500 Tote (Here lie 2,500 Dead) – the number differs from one mound to another, but all contain a staggering quantity of bodies.

It is a quiet place and, despite the area being surrounded by forest, I remember no birdsong. But it is also a loud place: the burial mounds in their size and simplicity, and the few stark words describing them, cry out across the years. You never forget visiting a place such as this, and having done so, I knew I needed to find out more.

As a 12-year-old, I knew next to nothing about the ethnic cleansing carried out by the Nazi regime. The rounding up and persecution of the Jews began in 1933. In the summer of 1941, when Germany invaded Russia, there began an ideological war between the two nations. As the German army swept east it was followed by the diabolical Einsatzgruppen. Formed into four units, their job was to round up Jews and other enemies and shoot them. However, the effect on the troops of having to execute tens of thousands of men, women and children soon led to low morale, suicides, alcohol abuse and desertion. The Nazi hierarchy needed to find a better way to exterminate the Jews. On 20 January 1942 a conference was held at a villa on the banks of the Wannsee in Berlin to decide how to do this. The outcome was creation of the death camps in which 1.7 million Jews were murdered in a systematic, industrialised process. By war’s end the Nazi regime had killed five million Hungarians, Poles, Russians, Gypsies, homosexuals, disabled people, and those considered Untermenschen (sub-humans), and six million Jews. Given the sheer numbers involved and as Germany collapsed it is hardly surprising that the task became impossible to hide; and so, on 15 April 1945, when the British troops entered Belsen they found more than 13,000 unburied bodies and some 60,000 emaciated, diseased people in a camp originally designed to house only 10,000. It left no one who witnessed this unmoved, and for many ordinary soldiers, who had slogged and fought their way from the beaches of Normandy to this awful place, it gave an unambiguous reason for going to war.

In the immediate days following the camp’s liberation, Brigadier Glyn Hughes, vice director of medical services for the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), managed the medical needs and organisation of the camp. During the first Belsen trial, he was a key witness for the prosecution, and when asked whether he had witnessed anything like Belsen before, replied:

“I have been a doctor for 30 years and have seen all the horrors of war, but I have never seen anything to touch it.“

Reading many of the transcripts of the trials of Belsen, it is still impossible to imagine what it must have been like. The details of these documents are so shocking and sickening that they belie the reality of the world in which most of us live. At the time of the liberation, 70% of the inmates needed urgent medical care. To facilitate this, they created a DP (displaced persons) camp nearby and drafted in medical people to look after the sick and dying. Among the medical staff were 96 student volunteers from London teaching hospitals, and it was their intervention that assisted in vastly reducing the casualty rate. Sadly, in the months following liberation and despite all efforts, more than 13,000 prisoners died.

The main problem was getting food into starving people. They tried three diets and ultimately decided on a Bengali Famine mix, successfully used during the highly controversial famine there in 1943. This proved to have some effect, and people recovered. There are conflicting reports about the effectiveness of this mixture, which comprised powdered milk, flour and lots of sugar, but as it was sickly sweet, many patients found it unpalatable. As most of the inmates were from Eastern Europe, they preferred a more acidic, vinegar and spiced diet, so to make the mix more palatable, they added paprika, which seems to have had a positive effect. Reading the evidence accounts, the recovery was a mixture of medical care, other rations, clean water to drink and “hope”. For those too weak to eat, they attempted intravenous feeding, but as SS doctors had murdered many prisoners using injections of benzol and creosote, at the sight of the feeding equipment, these people became hysterical.

So how did Belsen become the infamous symbol of this Nazi genocide? Following the invasion of Poland in 1939 the barracks at Belsen, which had been a camp for workers constructing the military base nearby (Belsen was a famous Panzer training ground), became a POW camp. The camp grew following the invasion of Russia, and at its peak housed more than 100,000 prisoners in three Stalags (prison camps). The Wehrmacht (regular German army) ran these Stalags and harshly treated the inmates: by war’s end, some 50,000 Russian POWs had died in Belsen.

In 1943 part of the camp came under the control of the SS department, euphemistically called, “the Economic-Administration Main Office”, and became part of the concentration camp system – in total there were some 20,000 concentration camps controlled by the SS. They designated Belsen a civilian internment camp and initially housed Jewish prisoners intended for exchange with German interns from other countries, and for hard cash. By concentration camp standards, many of these prisoners were less harshly treated because of their perceived transfer value, but, through this exchange programme, fewer than 2,500 Jews were freed.

The SS sub-divided the camp into smaller units for individual groups: the Hungarian camp; the Special camp – for Polish Jews; the Neutrals camp; and the Star camp – for Dutch Jews. That summer, some 14,600 Jews, including nearly 3,000 children, arrived. Most of these people were set to work; the majority salvaging usable leather pieces from shoes brought in from all over Germany and occupied countries.

By March 1944 they re-designated Belsen as a “recovery” camp and housed prisoners from other camps too sick to work, under the auspice that they would return to their former places once better. Naturally, the SS denied any medical treatment and so very few ever returned to their work camps, most dying from disease, starvation and exhaustion.

In August 1944 they formed the Women’s camp; the first inmates came from the Warsaw Ghetto. The most famous inmate of this camp was Anne Frank who, with her sister Margot, arrived from Auschwitz; both dying in March 1945, probably from typhus.

At no time was Belsen designated a death camp in the way of Auschwitz, but they sent there many inmates from Belsen for immediate execution and cremation. In December 1944 the new commandant, Josef Kramer, arrived from Auschwitz and it was during this time the camp unravelled as it took in tens of thousands of prisoners from the east, transferred away from the advancing Russian army – on the “Death Marches” from the east thousands of concentration camp inmates and Allied POWs were herded west in freezing, bestial conditions. My uncle, a POW in Poland, took part in such a march and credited his survival to a new pair of boots his mother had sent him through the Red Cross, which he received just days before they left.

On 5 February 1945, lice-infested Hungarian prisoners from the east brought with them typhus, which then raged through the camp decimating the already weak and sick.

It was this virulent outbreak, together with the infestation of lice and the sea of filth that enveloped this wretched place, that led the liberating authorities to order Belsen’s destruction by fire in June 1945. Flame-throwing Bren gun carriers and Churchill Crocodile tanks laid waste: a befitting end to a hell on earth. Flying overhead that day was comedian Michael Bentine on his way to Denmark with pilot, Kelly, who remarked on seeing the flames and destruction: “Thank Christ for that.” Bentine said that Kelly’s words sounded like a benediction.

Prior to the camp’s destruction, the Number 5 Army Film Unit made a film and photographic record of the conditions at the camp which have been seen all over the world and have made Belsen a synonym for Nazi crimes during the war.

In the aftermath, they rounded up former officers and guards and put them on trial. In all there were three Belsen trials, the first lasted 54 days and prosecuted 45 individuals, including Josef Kramer. At its conclusion, they sentenced 11 to death; they acquitted a few, and the rest were sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from one year to life. But by June 1955, through pleas for clemency and appeals, they had released all those imprisoned. There was only one trial in a German court and that ended in acquittal. More than 200 other named SS personnel known to have been at Belsen never stood trial. Although the Nuremberg trials found that the actions of the Wehrmacht in the treatment of Russian POWs constituted a war crime, no trials took place for those atrocities.

For years after Anne Frank’s death, Nazis sympathisers declared that she never existed and that her diary was a fake. Doubters challenged the Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal to track down her arresting officer, Karl Silberbauer – which he did in 1963. Shown a photograph of Anne, Silberbauer confirmed her identity. On the death of Anne’s father, Otto, in 1980, he bequeathed her papers and diary to the Dutch Institute of War Documentation which ordered a full forensic examination. At its conclusion in 1986, the documents were declared genuine.

An entry from her diary foretells a future still tarnished by the hatred, intolerance and violence of mankind: on 3 May 1944, she wrote:

“There’s in people simply an urge to destroy, an urge to kill, to murder and rage, and until all mankind, without exception, undergoes a great change, wars will be waged, everything that has been built up, cultivated and grown will be destroyed and disfigured, after which mankind will have to begin all over again.”

Note: We’ll never know the true figure of how many were killed during the Nazi genocide. A best guess is about 11 million, but that does not include many of the Russian POWs who died in captivity. Now we are nearly a century away from these crimes, it is important to note that many of the victims were Germans and that in the final months of the war, as Allied troops entered Germany, many vile crimes were committed by them on German civilians. I dedicate this essay to all victims of war crimes.

Tim Wickenden, 13 April 2020.

Learn more:

Imperial War Museum – www.iwm.org/history/the-liberation-of-bergen-belsen

Belsen Museum – bergen-belsen.stiftung-ng.de/en/your-visit/

Anne Frank – annefrank.org

The World Holocaust Remembrance Centre – yadvashem.org

auschwitz.org

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust – hmd.org.uk

The Holocaust Education Trust – het.org.uk

Archive film and photographic evidence, including Richard Dimbleby’s report, can be found on YouTube.com

Tim Wickenden was born in 1962 and has been a hobbyist writer since his teens, writing many short stories and a number of plays. He lives in the fabulous town of Fishguard and still works as a carpenter/furniture maker, writing in the afternoons, evenings and weekends. Tim always finds time to spend with his autistic 12-year-old son, playing games on the PS4, going swimming and walking. If you want to know more about his work, he can be found on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and his author website is www.timwickenden.com.

Great piece, thanks Tim

Very timely, especially as people are reacting against refugees.